The Most Incredible Fasting Study I’ve Ever Read

Main Points

Fasting appears to initiate fat release through classic lipolysis but then hands the job to lipophagy—an autophagy-based system that can move far more lipid as a fast deepens. Human adipose shows increased expression of autophagy-control genes with prolonged fasting, and ex-vivo (outside the body) inhibition of autophagy reduces fat release, supporting translational relevance. Practically, this means that as glycogen wanes and fat takes center stage, your body activates a higher-capacity pathway to keep energy flowing; it’s a mechanistic explanation for why longer fasting windows can feel metabolically “different,” but it isn’t a directive to fast—just a window into how your biology adapts when you do.

A new human-supported, animal-tested study [Study 534] shows that fasting doesn’t just turn up the usual fat-burning machinery—it shifts fat cells to a different, faster pathway for releasing stored fat. Instead of relying only on classic “lipolysis” enzymes, fasting increasingly recruits an autophagy-based route (technically, lipophagy) to mobilize energy. That hand-off helps explain why fat loss can accelerate as a fast deepens.

First principles: how fat normally leaves a fat cell

When you stop eating (no calories), fat cells begin exporting stored fat to fuel other organs.

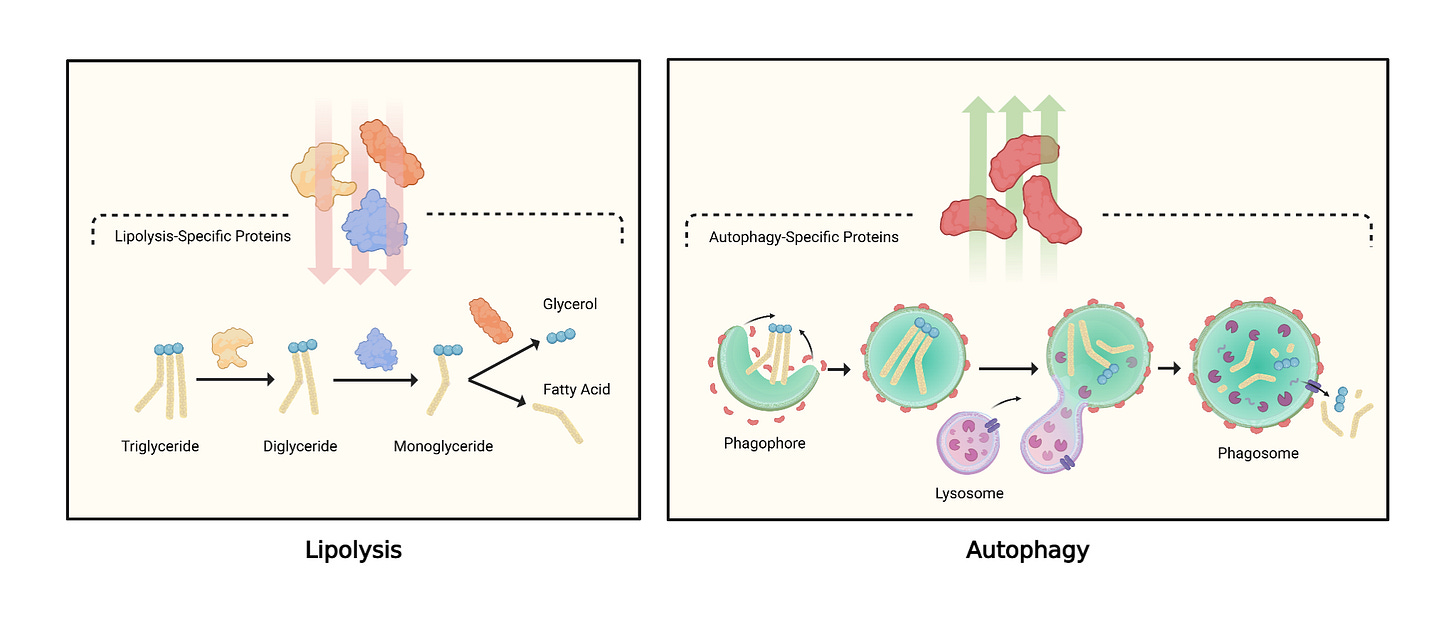

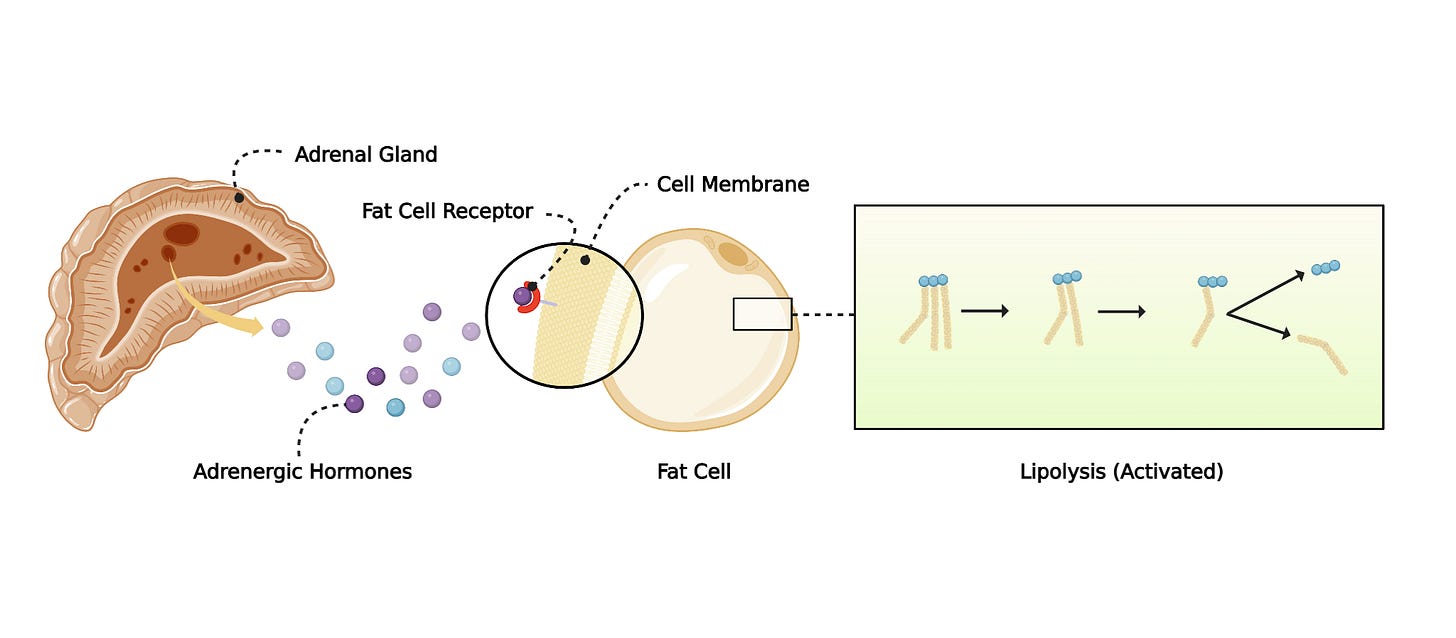

Lipolysis (the classic path): enzymes such as ATGL/HSL break triglycerides (fat) into free fatty acids and glycerol.

What the study observed: during fasting, several lipolysis enzymes weren’t elevated as expected. Instead, proteins tied to autophagy—the cell’s “recycling” system—rose. In this context, autophagy forms vesicles that engulf lipid droplets so they can be broken down and released.

Key terms

Autophagy: a cellular clean-up and recycling process that packages material into vesicles for degradation.

Lipophagy: autophagy specifically targeting lipid droplets to liberate fat for energy.

Glycogen: stored glucose; your body tends to use this first early in a fast.

The metabolic hand-off: lipolysis → lipophagy

Early in a fast, hormones (e.g., catecholamines) bind fat cells and trigger classic lipolysis. As fasting continues, the stimulus changes and fat cells up-regulate autophagy machinery. Functionally, it’s like opening a dam wider: lipophagy can process large chunks of fat at once, relieving the “throughput bottleneck” that would otherwise require huge amounts of lipolysis enzymes to keep up. In short, the canonical path is too slow alone; the autophagy system steps in to supercharge fat release when the fast deepens.

Why switch at all?

The most plausible explanation is efficiency under changing fuel needs. Early on, the body can still lean on glycogen (stored carbohydrate) and a modest fat trickle. Once glycogen dwindles, the energy demand shifts heavily to fat. At that point, an autophagy-based mechanism is better suited to move large lipid loads quickly and consistently.

What happens when you block autophagy?

How is autophagy controlled?

What happens to the body when autophagy is inhibited?

All of that is included in the complete analysis, along with access to a private podcast, live sessions with me, a library of articles and videos, and much more as a Physionic Insider :

Human clues that the same thing happens to us

We can’t run invasive experiments in people the way we do in animals, but we can look for molecular fingerprints. In individuals who underwent prolonged fasting (e.g., ~10 days), the expression of multiple autophagy-controlling genes in adipose tissue increased, aligning with the animal findings. In complementary ex-vivo tests, blocking autophagy reduced fat release from human fat samples in a nutrient-deprived state—further supporting a functional role for lipophagy in human fat mobilization during fasting.

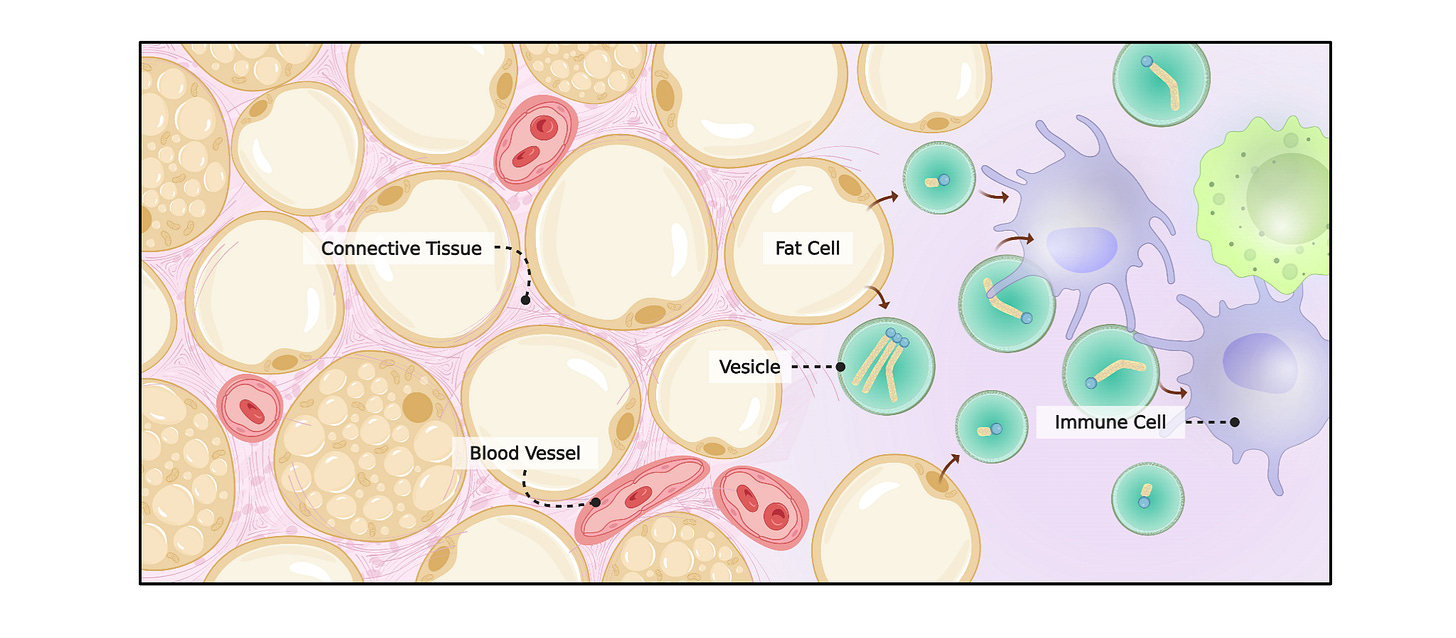

A note on immune–fat cross-talk

Prior work has hinted at “conversations” between fat cells and immune cells during fasting: fat can be exported in vesicles that immune cells take up, potentially handling that load via their own autophagy programs. This dovetails with the idea that fasting coordinates multiple tissues to manage energy flux

What this does—and doesn’t—mean for you

This is a mechanistic advance, not a prescription. It suggests that:

Deeper into a fast, fat cells rely increasingly on lipophagy to free stored fat.

The quality of fat mobilization changes as a fast progresses, which may explain why longer fasts can feel metabolically different from short ones.

It does not dictate that everyone should fast, nor does it set an “optimal” fasting length. It simply clarifies how your body makes a bigger metabolic gear available when food is absent.

Main Points

Fasting appears to initiate fat release through classic lipolysis but then hands the job to lipophagy—an autophagy-based system that can move far more lipid as a fast deepens. Human adipose shows increased expression of autophagy-control genes with prolonged fasting, and ex-vivo (outside the body) inhibition of autophagy reduces fat release, supporting translational relevance. Practically, this means that as glycogen wanes and fat takes center stage, your body activates a higher-capacity pathway to keep energy flowing; it’s a mechanistic explanation for why longer fasting windows can feel metabolically “different,” but it isn’t a directive to fast—just a window into how your biology adapts when you do.

What happens when you block autophagy?

How is autophagy controlled?

What happens to the body when autophagy is inhibited?

All of that is included in the complete analysis, along with access to a private podcast, live sessions with me, a library of articles and videos, and much more as a Physionic Insider :

Dr. Nicolas Verhoeven, PhD / Physionic

References

[Study 534] Naveen Kumar GV, Wang R-S, Sharma AX, et al. Non-canonical lysosomal lipolysis drives mobilization of adipose tissue energy stores with fasting. Nat Commun. 2025;16:1330. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-56613-3

Funding/Conflicts: Public Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: KL2 TR002542 (to P.K.F.); R01 DK137913 (to M.L.S.); no other public grants are listed.; Non-Profit Funding: No non-profit funders are listed; no non-profit grants are disclosed in the acknowledgements.; Industry Funding / Conflicts: The authors report no industry funding for this study; outside the submitted work, P.K.F. reports consulting for Regeneron; advisory board service for Camurus, Crinetics, and Amryt/Chiesi; and research funding from Crinetics, Corcept, and Quest; all other authors declare no competing interests.